Introduction

Phytophthora cinnamomi Rands (1922)

Phytophthora cinnamomi

was first described on Cinnamomum

burmannii by Rands in Sumatra (

Cultural Characteristics

Cultures show profuse tough aerial mycelium that sometimes grows in a rosette pattern (Fig. 2). The minimum temperature for growth is 5–6°C, the optimum temperature for growth is 24–28°C, and the maximum temperature for growth is 32–34°C. There is no colony growth above 35°C.

Reproductive Structures

Asexual Structures

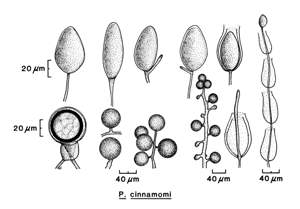

Sporangiophores:

Sporangiophores are thin (3 µm in diameter). They exhibit simple or sympodial

branching and typically proliferate through the empty

sporangium.

Sporangia:

Sporangia form only in aqueous solutions. They are

nonpapillate and ovoid, obpyriform, or broadly ellipsoid. Sporangia are an average

of 40 ×

75 µm (Fig. 3). Apical thickening is slight and noncaducous.

Chlamydospores:

There are grapelike clusters of thin-walled

chlamydospores (Fig. 4).

Hyphae:

Hyphae on malt agar are coralloid (i.e., with frequent, rounded nodules), becoming broad (8 µm wide) and very tough (Fig. 5). Hyphal swellings are typically spherical (average 42 µm, maximum 60 µm in diameter) and in clusters, and the wall is not very thick.

Sexual Structures

P. cinnamomi is

heterothallic.

Oospores form in intraspecific matings and in crosses with

P. cryptogea.

Antheridia:

Antheridia are

amphigynous and long and average 17 × 21–23 µm.

Oogonia:

Oogonia are round and smooth walled with a

tapered base. They are hyaline to yellow-brown with age and 21–28 µm in diameter.

Oospores:

Oospores nearly fill the oogonia and are round and

plerotic. The average diameter is 35 µm. The wall is colorless and 2 µm thick

(Fig. 6).

Host Range and Distribution

The pathogen causes disease on pineapple (Ananas

comosus); Lawson

Symptoms

The pathogen has a saprophytic phase and can survive in dead plant materials for years. Sporangia release zoospores into the soil that can infect roots. Propagules can also be splash dispersed to the aerial parts of plants. The pathogen can also infect leaves, stems, fruits, and pods.

Symptoms vary with the host infected,

but in general, the pathogen can cause a root rot that leads to wilting and

dieback of the plant (Figs. 7–9).

P. cinnamomi causes a rot of fine feeder roots that leads to dieback.

Wilt, stem cankers, decline in yield, decreased fruit size, gum exudation, collar rot near graft lines, and heart rot are also symptoms

In pineapple, heart rot can be detected when the crown leaves turn from their normal green to a yellow or reddish color; also, these leaves can be easily removed when pulled. The pathogen infects the roots of kiwifruit trees, causing bark sloughing and exposing black-stained vascular tissues. When camellia plants become infected, depending on the severity of infection, leaves can become yellowish green and plants become stunted, gradually wilt, and eventually die.

Diagnostics:

Plant foliage becomes chlorotic, wilts, and dies back rapidly when root rot

occurs. Occasionally, the infected plant suddenly collapses, but the plant can

live for several years, especially in cooler and damper environments. Movement

of symptomless plants is often the major source of spread of

P. cinnamomi.

References

Erwin, D. C., and Ribeiro, O. K. 1996.

Phytophthora

Diseases Worldwide. American Phytopathological Society,

Mehrlich, F. P. 1932. Pseudopythium phytophthoron, a synonym of Phytophthora cinnomomi. Mycologia 24:453-454.

Rands, R. D. 1922. Streepkanker van Kaneel, veroorzaakt door Phytophthora cinnamomi n. sp. (Stripe canker of cinnamon caused by Phytophthora cinnamomi n. sp.), Meded. Inst. Plantenziekten 54. (In Dutch)

Sideris, C. P. 1929. Stem rot of pineapple plants. (Abstr.) Phytopathology 19:1146.

Stamps, D. J., Newhook, F. J.,

Waterhouse, G. M., and Hall, G. S. 1990. Revised tabular key to the species of

Phytophthora de Bary.

Mycol. Pap. 162.

CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom;

Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew,

Waterhouse, G. M.

1963. Key to the species of

Phytophthora de Bary. Mycol. Pap. 92.

CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom;

Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew,

Waterhouse, G. M., and Waterston, J. M. 1966. Phytophthora cinnamomi. CMI Descr. Pathog. Fungi Bact. 113:1-2.

Zentmyer, G. A. 1980.

Phytophthora cinnamomi and the diseases it causes. Monogr. 10. American

Phytopathological Society,